Collaboration between different species is a less-explored factor that contributes to the diversity of life.

A special group of insect protectors might be guarding the cherry tree in your garden or the maple tree down the street.

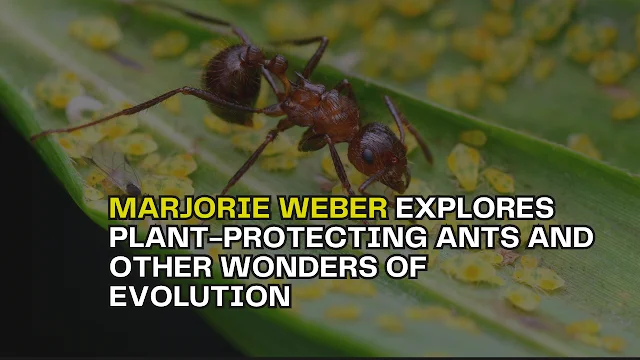

Mites act as plant guardians by eating fungi that can harm leaves, just like sheep graze on grass. Meanwhile, ants keep watch on branches, ready to bite or sting caterpillars, and sometimes even elephants! In exchange for this protection, plants provide these helpful insects with food and a place to live.

This incredible teamwork between plants and insects has developed countless times, explains Marjorie Weber, a scientist who studies how living things have evolved at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Surprisingly, plant protectors are all around us, but most people don’t even notice.

Weber has always been fascinated by “strange, interesting, and overlooked species.” When she was a child, she loved creatures like roly-polys, earthworms, beetles, and spiders. Yet, more than individual bugs, she is captivated by the amazing variety of life on Earth. She wonders: How did this immense collection of species come to exist? When it comes to biodiversity, Weber is full of questions: Why do we have so many different types of flowers? Why are there millions of insect species compared to relatively few species of sharks? Why did some branches of the tree of life flourish while others faded away? “I’m just really passionate about these big biological mysteries,” she says.

Her office at the university is just like what you might picture for someone enchanted by the natural world. A tall fiddle-leaf fig stands near her desk, and potted plants fill the window. The walls are adorned with science art: a hanging print depicting the evolutionary history of flowering plants, a large image of a sparkling orchid bee, and an illustration of Charles Darwin with his famous finches peeking out from his beard.

Since Darwin’s era, scientists exploring the forces behind evolution have mainly concentrated on conflicts between species, such as finches vying for seeds and the ongoing battles between predators and prey. The significance of cooperation in evolution was sometimes underestimated, partly because it was seen as a more feminine viewpoint, according to Weber.

Weber’s research group delves into the role of cooperation in driving evolution and biodiversity. She dedicates her time to observing interactions between plants and arthropods in the field, greenhouse, and laboratory. Additionally, she utilizes computational methods to analyze patterns of evolution.

Weber is recognized for her research on extrafloral nectaries, which are nectar-filled bumps protruding from leaves and stems on certain plants. These sweet snacks attract ants, creating a partnership where ants defend the plants from harm. Weber studied extrafloral nectaries in present-day vascular plants and traced the evolution of this trait in ancient plant species. She found that the development of this trait was a winning strategy in evolution. Once these sweet structures appeared on a particular branch of the plant family tree, that branch rapidly accumulated more species. This suggests that the chance for plants to exchange nectar for insect protection played a role in encouraging plant diversity.

Certain plants create sweet structures (green circles) that attract ants. These insects shield the plants from harm, showcasing a special teamwork between ants and plants that has occurred frequently over time.

Judith Bronstein, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Arizona, remarks that Weber’s findings were unexpected. While scientists might anticipate that a specific adaptation, like extrafloral nectaries, helps a plant survive and increase in numbers, the reason for the multiplication of plant species remains unclear. Bronstein emphasizes the intriguing aspect that having extrafloral nectaries seems to lead to diversification. She sees Weber’s work as distinctive for its ability to weave together scientific ideas into something “completely new and completely different,” showcasing how innovation occurs in their field.

Weber is also making significant contributions beyond her research. In 2018, she played a key role in co-founding Project Biodiversify. This program is dedicated to ensuring that biology education is not only accurate and engaging but also strives to be “as equitable and inclusive as possible,” according to Weber.

Weber didn’t envision herself as a scientist when she was young. Growing up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, she didn’t see many examples of women scientists, and science wasn’t on her radar as a potential career. However, everything changed during a biology course with spider scientist Greta Binford at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Ore. “Understanding that was a task, and seeing her do it was really important for me,” Weber explains. Binford allowed Weber to work in her lab, focusing on studying brown recluse spiders. Binford encouraged Weber’s interests and “went out of her way to convince me that I was smart enough and could do this,” she says.

Years later, after Weber established her own lab, she and her colleagues decided to look into how well college biology textbooks showcased a diverse group of scientists. The findings, reported in 2020, highlighted a significant mismatch in demographics between scientists featured in textbooks (mostly white men) and the students using them. Weber’s team is actively working to address this gap by creating resources for teachers that showcase a diverse group of role models in biology.

Weber hopes to encourage students to explore how the world works. Ecologist Eric LoPresti, a former postdoc in Weber’s lab at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, describes her as a “fantastic adviser.” She fosters a supportive community, ensuring everyone feels included, and LoPresti has tried to replicate this culture in his own lab.

Weber’s advice for young people is to observe and take note of what sparks their excitement—perhaps they’ll come across a curious group of ants marching up and down a tree. “That’s what it really means to be a scientist,” Weber says. “Follow those feelings of wonder and ask lots of questions about the world with your eyes wide open.”

Marjorie Weber

Assistant Professor, also in charge of Graduate Studies she/her.Education/Degree:

Research Areas and Fields of Study.

- Evolutionary Ecology

- Community Ecology

- Plants insect interactions

- Macroevolution

- Inclusive biology education